|

by Kent Aitken |      |

Every time I read an article about Gen Y or Millenials I run it through this litmus test: throughout the text, can you replace "Millenial" with "employee" with no loss of meaning?

“[Employees] want meaningful work, they want to do things that are making an impact and if they’re not in a good environment where they can do that, they’re always going to be looking for something else"

From this piece, which was - sadly - actually about Millenials.

Of course, there are legitimate and meaningful trends and changes occurring, even about Millenials (I'd give more credence to this idea about changing prioritization between work and family life). But it's worth it to be skeptical, to put ideas in broader context, and to look for what's truly meaningful.

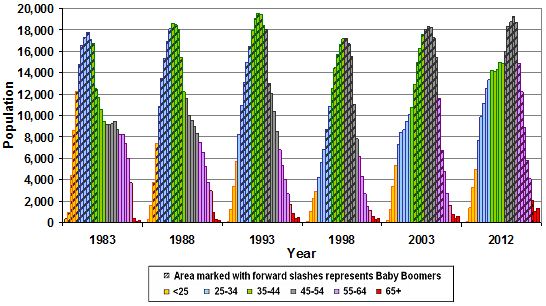

Baby boomers are retiring, or about to. Deloitte has suggested that this wave of retirements has been delayed slightly - by "better than expected health" and "worse than expected wealth" for would-be retirees - but here's the demographic profile of the public service up to 2012, Boomers identified by forward slashes:

Over the next decade, we're going to see a demographic shift in key positions throughout the public service. But the question is: does that matter?

And why?

The Perimeter of Ignorance

Here's my frontrunner idea for why it might. I don't think living in the age of information leads directly to collaboration as a first-order condition. Instead, I see collaboration as a second-order condition of a more fundamental result: being constantly reminded of one's ignorance. Collaboration is a symptom, in this view.

Admittedly, this isn't really new. It's not like there was a period of human history in which our knowledge was static. The idea of heliocentrism, for example, would have been world-shattering, dramatically changing the parameters within which people constructed their beliefs. But it seems as though people throughout much of history always considered that the universe ended where their knowledge did, simply expanding the universe slightly when their knowledge grew.

"It's Like Lego."

I simply think that the recognition - deep-seated, not just logically, on principle - that we don't know everything has taken hold, and reached much further into the bulk of populations. The plural of anecdote is not evidence, but this has been on my mind lately:

- In the last few weeks I've met two people whose lives' work was connecting people, based on the idea that all the building blocks for building a better society are already there, the question is simply one of assembly. "It's like lego."

- Lately I've had the opportunity to help colleagues with marketing campaigns, internal strategies, and policy presentations, somewhat awed by the idea that I had something to contribute to any of these.

- Last week Tariq posted about Planning and Idea Generation in Government, in response to Chelsea's point that even deciding that something is a good idea is a muddy and difficult process.

- Which led to a conversation about decision-making models. Some very (very) smart people were debating their merits. One view would be that they're a useful heuristic, and I'd add that their existence and popularity is based on a recognition that we'll muck things up simply by throwing neurons at problems. But at the same time they have limits, and over-reliance can lead to sub-optimal results.

Or, this, from Joeri van den Steenhoven from the MaRS Solutions Lab:

"We never have all the knowledge in place. So we have to learn... Mostly, it's about organizing a learning process for the stakeholders and users involved, and trying to find out together how we can bring about successful change."

Strategy in a Gigantic Universe

I didn't intend this when I started writing, but this gets back to the last few weeks of posts: Nick on Blending Public Sentiment, Data Analytics, Design Thinking, and Behavioural Economics, or me on Building Distributed Capacity. These posts could be read as buzzword-heavy, or as reasonable management strategies in a world where solutions are elusive, subjective, and fleeting. As ways to, as Josh McManus suggests:

What do you think? Is increased recognition of our limits a genuine shift? Or am I unfairly assigning importance, or missing longer-term context? Is a more collaborative, tentative approach to solution-generation actually a characteristic of those people who'll be replacing retiring Boomers?

And what would that mean for the public service?

I think it's important to look at possibilities and plausibilities for the public service in the long term. To be perfectly honest, my interest in determining whether or not this idea means anything is partially driven by the conversations that came out of George's leave and Nick's interchange from the public service. It seems staying or exploring opportunities elsewhere is on many people's minds.

That's quite alright. We can go "from Public Service to public service," as George put it. But I'm interested in at least complicating these decisions by pointing to opportunities for positive change in the public service. It seems to be the problem I've fallen in love with.