| by Melissa Tullio |    |

I left a comment on Kent's recent post (See: The Future Of Online Communities) that was probably out of scope of what his post was about, and started reflecting on engagement in digital spaces versus in real life. Here's a challenge question I started thinking about: "How might we make the best use of technology/online systems to capture public sentiment and insights in a deeper way?" (I'm not going to attempt to navigate that one in this post, but maybe a future post.)

I think the key to this is something Kent also asked, which got me thinking in a different direction: "The question [about online collaboration] will move from 'How can we get people to engage?' to 'Who actually needs to engage, and why would they, in particular?'"

There's an assumption we make in government, especially in the communications world where I work, that whenever we make an announcement or hold a consultation, people are engaged and interested and will come. This isn't generally a bad assumption to make. We do get engagement; we do get people at the town halls and consultations we run. But the people who attend often represent people who we've heard from, time and again, over the years. The outcome of these consultations is almost completely predictable - we issue management the hell out of it; we can anticipate responses, and come up with plans to "mitigate" them.

So my next challenge question would be, "What's the point?" If you're doing a consultation and you know what you're going to hear, isn't it a big waste of time and resources to do it? Can't we do it in a more meaningful way that generates new solutions or ways to work together?

Beyond the Usual Suspects

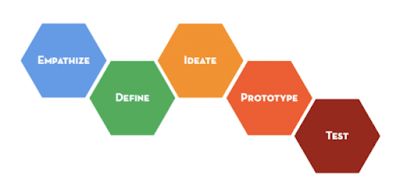

One thing about design thinking that's different than other problem solving methods is taking time to interview and empathize with extreme users. It's crucially valuable to do this because taking time to reach out to, and empathizing with, extreme users helps to reveal the deeper, more systemic challenges in the design of your service/program.This type of ethnographic research is not something we normally do enough of in government. We tend to create policies/programs that end up working for the mainstream user. The way we come to create programs is based on well researched best practices (i.e., existing solutions), which inevitably leaves some users behind in the process. This approach doesn't include extreme users in the problem definition stages (or problem solving stages), so we assume that what we design is good enough, without examining all those hidden assumptions we're making. The kind of research and deeper understanding that you need to do to really empathize with service users requires time, and in a lot of our work in the policy making environment (and exponentially more in the communications space), time is (artificially) something we don't have1.

Another challenge isn't just the process/resource barrier in government work from doing this kind of research. Even if you design a program/policy to include time for this kind of deep dive research, how do you make the case for people who you don't normally interact with to gain your trust and let you into their spaces?

What's In It For Them?

When I previously worked in an HR role for Ontario, I was one of the people responsible for the formal employee recognition program. Something we constantly struggled with was how to tap into people's intrinsic motivation for doing things. There are a lot of smarter people than me who have done research in this area, and the short answer is, "it's complicated." I was most interested in what motivates people to engage and interact with online spaces because another file I worked on was an ideas management system, and I was curious about why these kinds of systems often fail.Something my team learned is that online engagement is limited. Taking idea generation to the next level requires an in person component that can't be replaced by online platforms (not yet, anyway). An ideas campaign, followed by observational/ethnographic research to figure out what you're missing, followed by a hackathon/jam/competition of some sort to test some theories, followed by an experiment/prototype-making stage, followed by reflections/sharing lessons to improve something, is what you need to make the campaign work through the full spectrum of engagement.

That goes back to the old constraint: who has time for this?

Online and in-person engagement

From everything we learned, online platforms simply aren't enough; some tangible, shared outcome from the ideation or consultation stage is needed in order for people to believe you're doing something for them, or else they lose faith and you lose credibility (See: Pulling the Trigger on Chekhov's Gun). Many people are happy with engaging online at the front-end - it's low-friction and easy (also less valuable to gain deeper insights); extreme users, the ones we need to take time for to understand better, need more (and so do we if we want to reach those deeper insights to design things better).Any online or offline engagement platform not only needs to ask the question, "who needs to engage?" but "who else needs to engage who isn't already raising their hand to volunteer?" Knowing how to answer the corollary question, "how do we motivate them to?" is definitely the tougher one.

1. I'd say resources (people/funding) are something we have less and less of in a more real way than time; time for empathy/good design can be worked into our processes (assuming we've taken a good look at our culture and we're able to move towards changing it to include mindsets like human centered design in our work). ↩

Nice blog you have here, thanks for sharing this

ReplyDelete